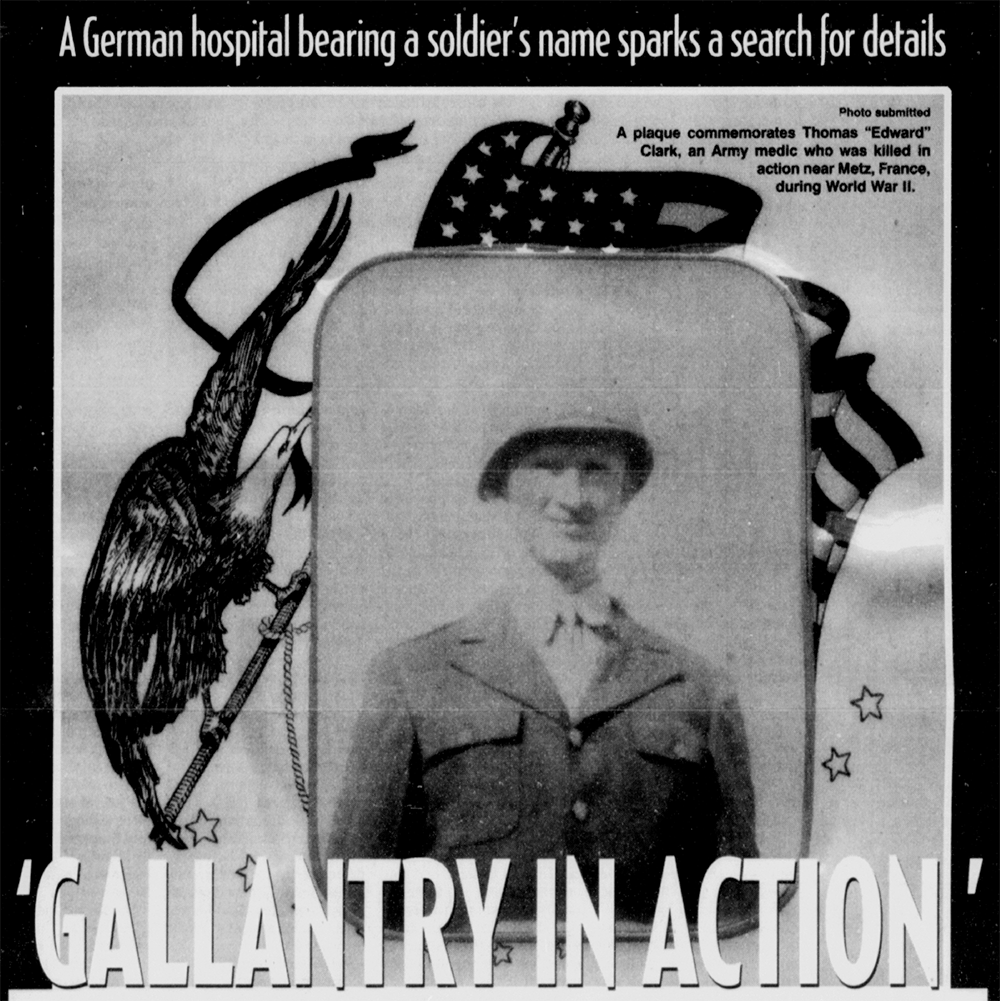

Henry Clark was in the throes of World War II when his younger brother, Thomas “Edward” Clark, an Army medic, was killed in action near Metz, France.

Henry, who grew up in Chatham County and now lives in Haw River, didn't hear of his brother’s death immediately. He hadn’t yet returned from the war when the news hit home. He later only learned a few details and none of them included that an Army hospital in Frankfurt, Germany once bore his brother’s name.

But it's a legacy that a dedicated Army chaplain on a personal mission, of sorts, worked to keep alive in the late 1980s. It s also one that Henry’s cousin, Barbara Pugh of Pittsboro, recently resurrected with a paper trail that starts with a 1944 Western Union telegram informing the Clarks of Edward’s death and ends with an e-mail written this past April explaining what became of the 97th General Hospital named Clark Kaserne.

Henry was drafted into the Army before Edward, who was drafted in February 1942. Henry, a corporal with the 840th Aviation Engineer Battalion, drove a truck. His brother, four years his junior, drove an ambulance for the Medical Section, 15th Tank Battalion, 6th Armored Division. While they fought in the same war and in the same armed service, their paths only crossed a couple of times in England and then in France in the summer of 1944. Henry didn’t know the visit would be his last one with Edward, who at age 21 was killed by a land mine after he rescued several wounded men on Nov. 24,1944.

The Rev. Bertin Samsa, now a priest at a Catholic church in Weyauwega, Wis., was a lieutenant colonel in the Army serving as a chaplain in Frankfurt. Germany, in the late 1980s when he became interested in Edward Clark’s history. Samsa knew the 97th General Hospital was named "Clark Kaseme" but there was no other information available. There was no plaque or any explanation about why the German hospital captured by U.S. Forces during World War II bore Pvt. Thomas Edward Clark’s name.

"I didn’t know who Clark was,” Samsa said. "If the thing had been named for Mark Clark, the famous general, there would have been a picture or a statue or a plaque, at least, about him.” But Edward Clark was just "a lowly soldier,” Samsa said, and he was determined to give the private, who was killed in action, the honor he deserved. Samsa turned to his typewriter during his personal time and wrote more than 17 letters between May 1987 and May 1989 in his quest for information, always saving the carbon copy of each, which he kept in a file.

From the U.S. Army Institute of Heraldry to the National Archives in Washington, D.C., to the National Personnel Records Center in St. Louis, Mo., to the Veteran’s Administration in Atlanta to Henry Clark in Haw River, Samsa searched for records, photos and memories in an effort to piece together Edward Clark’s history.

"We wish to erect a plaque in his memory," he wrote to the Veteran’s Administration Jan.12, 1988. “We ask that if you have any pictures or information pertaining to his decorations and awards, please help us in our endeavor to render honors to the man after whom this Kaserne was named.” Samsa wanted to inspire the young, first-year medics stationed in Germany with Clark’s story and since the chapel was undergoing renovations at the time, he planned to dedicate a wall in the building’s foyer with a plaque and picture to "educate the troops about Private Clark."

He gradually learned the details he was seeking. Many of them arrived with a letter from Mary Bridges, of Lemon Springs, Henry Clark’s niece. "I am writing on behalf of my mother, Bronna Clark Kimball,” she wrote in a letter dated April 14, 1988. “We appreciate so much your letter of (Feb. 4, 1988), your interest in my uncle, Thomas E. Clark, and your untiring efforts to locate his family and pertinent information about him. ... I’m enclosing all of the information we could find in my grandmother’s personal effects.” Bridges sent Samsa the Western Union telegram informing Eli and Daisy Clark their son was killed and the letters that followed from the Adjutant General at the time, the deputy director of the Army’s Personal Affairs Division and from Chaplain James W. Wright, who wrote to the family Dec, 20,1944, from "somewhere in France." "(Edward Clark) will never be forgotten as long as one of his Army associates is left, for he was truly respected and loved by all — both officers and men — for his remarkable personality and character.

“May I add that as his chaplain, I personally knew him and admired him for those inner qualities of faith that he revealed to me on many instances,” Wright wrote. “He died bravely and courageously —‘He died that we might live."

IN APRIL 1945. another letter arrived from the Adjutant General’s office, informing the family that Edward Clark was awarded the Silver Star and the reason he was honored for his “gallantry in action.” "On five occasions on (Nov.15,1944), Private Clark crossed a bridge through a hail of enemy fire and evacuated wounded soldiers who had fallen while attempting to establish a bridgehead,” the citation states. Less than 10 days later, Clark entered an area deemed “no mans land” deep in the woods to evacuate casualties, even though he knew it was “heavily defended by the enemy and mined heavily." Clark drove his ambulance into the woods and then traveled on foot to rescue the wounded. “After administering life-saving first aid, he carried the men to his vehicle," the citation states. “On leaving the area, his vehicle struck a mine and Private Clark was killed. The wounded men, however, were saved, despite the mine explosion, and later evacuated to an aid station."

Another letter written to Eli Clark in Siler City from the War Department arrived May 13, 1946, to let him know that his son was buried in Limey, France, and that “in the near future, the War Department will receive authority to comply, at government expense, with your wishes regarding final interment."

Eli Clark didn't live to see his sons body returned home. The elder Clark died Sept. 15, 1948, and Edward Clark’s body arrived in Pittsboro on Sept. 16, 1948. They were buried with joint funeral rites Sept. 17, 1948, in the Pleasant Hill Methodist Church cemetery.

Samsa saved all the letters and documents Bridges sent and still had them this past March when Pugh contacted

him in Weyauwega, Wis., via email seeking his assistance. "I have been trying to reconstruct military records and document the family story that the 97th Hospital and Clark Kaseme did, in fact, relate to my ancestor,’’ Pugh wrote.

Pugh, a genealogy buff, started her search for information last year. She, too, was trying to piece together her cousin’s history, but all those precious family records — the letters and telegram — were sent to Samsa 20 years before.

She started instead with the government and quickly reached a dead end when she learned, through the National Personnel Records Center in St. Louis, that Army records from 1912 to 1959 were destroyed in a fire in July 1973.

But Pugh didn’t give up She turned to her cousin, Henry Clark, probing his memory for answers. Henry didn’t have many, but he did still have a copy of a letter that Samsa sent him in 1988. Pugh took the letter and turned to the Internet to find Samsa. After she found him and contacted him March 7, he quickly responded.

“Yes. I have a file that has been hanging in my file cabinet for years,” he wrote March 8. “I wonder why I never cleaned it out. Now I know the reason, hope it helps."

Samsa informed Pugh that a painting was made of Edward Clark, which was waiting to be hung in the foyer of the hospital when he was transferred to Fort Leavenworth, Kan., in 1989. “I left and it was still hanging in the chaplain’s office, waiting for a glass case to be made to protect the picture,” he wrote.

Samsa mailed the entire file with all the documents he collected, including General Order No. 83 dated July 29.1947, that officially declared that the area occupied by 97th General Hospital was named Clark Kaseme.

“Isn’t it amazing?” Pugh asked. “It was still in his file in Wisconsin.” When she received the coveted file from Samsa, she made copies of everything. She gave one copy of all the documents to Henry Clark and keeps another in a red notebook along with some photos of the facility and a final e-mail from Nicole Fries, in the public affairs office in the U.S. Consulate General in Frankfurt, Germany, dated April 1,2008.

“In October 2005, the U.S. Consulate General Frankfurt moved into the building complex that used to be the 97th General Hospital," Fries wrote in the e mail, providing Pugh with the final piece of the puzzle.

“You can’t imagine how happy I was when this came together,” she said. It also means a lot to Samsa now that he knows that an important part of history will be preserved. I didn't think he should be forgotten, Samsa said.